Note from author: I haven’t written anything creative over 1,000 words this year, but I did put together a mini thesis paper.

Abstract

The film meme data collection community is made up of anyone that posts memes showcasing their thoughts or feelings with films and television as the basis for the communication. Whether you’re mentioning an episode of Friends or utilizing a photograph of a politician juxtaposed to the latest comedic film, media is being used to communicate globally through our screens. In this paper, I will review the existing literature on film memes and examine the schools of thought, such as entertainment leisure, to focus on what this community is about and how the LIS profession meets their needs. Within the film literature, I will look at historically, how films are used to pass messages, the political nature of films and discussion, and finally the habits of the community. With the methodology and discussion I hope to delve into how social media is a driving force of this community and that any progress to the technology is something that must be at the forefront and available for information professionals.

Introduction

Do you enjoy watching movies? Have you ever been sent a meme where a movie has been manipulated to either tell a joke or relay a message? Was the message political in nature? What I was interested to learn with this research was just what memes were for. Not only in the historical sense, but also as from the point of view of data collection. If a large enough portion of the population relates to a joke that was created out of existing media that conveys a populace thought about our country at this particular point in time, isn’t that important? Before I began the research, I didn’t think I would find more than analyses of how people enjoy watching cat videos, what I learned was there is over a decade of research on this community and just how they affect the public landscape.

How many people have read the works of Oppenheimer in comparison to the number of people that now correlate Cillian Murphy’s look of panic prior to the bomb dropping in the “Oppenheimer” film with catastrophic disaster? Those familiar with the calculations of quantum physics may be small, but anyone who sees the still of that actor pressing his hand against his sweaty brow, understands that something huge was created that could affect the entire world. That is the power of media and how we utilize it to communicate with others. Information professionals are on the front line of seeing this dialogue in real time.

My literature review will look at the history of the community, the political leanings of memes that can be either grassroots, or created by a corporate organization, to the habits of the community. These three areas will be examined to shed light on the global impact of the community and then on a smaller scale, how it affects the community within their own towns, and are their needs being met by their local library.

With the methodology and discussion, I’m utilizing the school of thought outlined in Stebbins (2015) work on serious leisure and hobbies. Memes and the love of films definitely falls under this category and I will use his work as the foundation to look deeper at how it’s grown. When a hobby that’s used as a pastime on your phone draws the attention of corporate sponsors and government organizations, that’s the understanding that it’s no longer a small niche group, but it’s something quite important.

Where do memes belong in the social and political landscape? They’ve become a staple of social media and they show up as snippets on our news. Is it something that has grown beyond the community it originated into a part of our daily reading? I hope to gain a few answers, if not, the building blocks for further study.

Literature Review

This literature review will touch on the history of how film and television has historically been manipulated to communicate with the public, the habits of the information learning community, and finally the politics of this powerful tool that floods our screens.

The Sound of a Voice

Foster (2022) analyzed how the voice of women “were historically used—and still are—as assistants and phone operators”. If for fifty years, we are fed through the media that people should look and act a certain way, it becomes part of our belief system. Some creators have used the power of memes to showcase their own identity. Turner (2022) wrote that “The understanding of Carol as a Christmas film but also as a part of a wider season of celebration has been cultivated by fans through the sharing of memes” (p. 37). A film about queer characters had a fanbase that turned memes about the characters into a Christmas film; normalizing and making a film that was at times dark into something that belonged to them.

The example of memes of the film Carol mirror what happened with Penny Dreadful. Braid (2017) touches on how “Penny Dreadful’s appropriation of Shelley’s story seems to mend Frankenstein’s mistakes from the novel” (p. 235). Fans of Penny Dreadful wanted more pathos and a resolution to the monster actually being the doctor, which was worked into the adaptation. A hundred-year old novel, with the help of fans online, wish-fulfilled the monster being humanized. Lee (2015) described what happened with Penny Dreadful as “a form of non-linear cross-contamination that destroys the metanarrative of the originary text” (p. 13). Memes can be looked at as a contamination of the original text to fit a new narrative, but is this a bad thing? Not all original works will be manipulated into something positive, as this community often sees, it can be used in ways that far outreaches the scope of fandom.

In his explanation of Mark Twain’s “The War Prayer”, Eastman (2016) notes that “there is a lack of historical specificity within the text that readily permits adaptation to other moments of fervid, religious patriotism in the name of war” (p.79). Twain’s ambiguous novel has been used to push the adapter’s political beliefs. The meme community creates for their fellow readers, but what happens when the communication turns political?

The Power of the Community

The Norwegian government “conceptualize their social media strategies before the release of their films in movie theatres” (Holmene 2018 p.46). It’s presented as a way for independent films to get support from the government, but others see it as a way that corporations game the system. If there is a carrot used to weigh the suitability of art before it is presented to the public, is that a form of censorship?

Pang & Goh (2016) “found a myriad of political conversations happening on social media which shaped the public debate, preceded offline mass protests” (p. 546). The personal can turn political. O’Meara (2018) reported on how “news of Trump's so-called plagiarism spread quickly, with bloggers and journalists jumping at the opportunity to repost video comparisons or to contextualize Trump channeling a fictional villain” (p. 30). Making fun of the President through memes about the movie Clueless is something that is unique to the 21st century. Humor is a salve that can heal and grow a movement. Penney (2020) stressed “it is necessary to examine how everyday citizens make sense of their role in political discourse and how they engage with them – in their social media activities” (p.793). Political memes aren’t always just conversations, sometimes they’re movements.

In Indonesia, political parties use social media and the release of new films as a way to popularize their political figures in power. Schmidt (2022) explored how Indonesia used social media to make “these initiatives marked by an aesthetics of authority, which constructs traditional figures of Islamic authority as role models” (p.239). Hirsch (2019) argued that “treatment of such a mundane topic, especially compared to the original subject, forces changes” (p.27). This was concerning memes that had been created to parody the last days of Hitler. Similar to O’Meara’s musings, humor was used to collectively laugh at a harsh reality.

Humor isn’t the only outcome in politically-skewed memes. Nee & Maio (2019) reported on “the extent to which negative persuasive visual memes about Clinton incorporated gender stereotypes of females and female politicians” (p.308). Like the altering of women’s voices to fit a narrative in film, memes also can be used to minimize women on the political scale. How does this affect the film meme communities’ habits?

Habits of the Community

Faidley (2021) argues that “raising one’s consciousness requires challenging taken-for-granted assumptions” (p. 147). The power of controlling the narrative through the same image filtered through different apps was studied by her and her graduate class to analyze if the message of the film from the point of view of the filmmakers was the takeaway of the masses that posted about it. What does the community get from sharing memes? Burke (2022) researched “fidelity analysis with many participants articulating the role and importance of source text faithfulness in their vernacular adaptations” (p.87). He believed that how true fans kept their adaptations to the original source material showed their appreciation as much as it did the power of that media’s message. Pop (2015) stated, “memes are cultural replicators, units of culture that are transmitted via imitation and which are subsequently “selected” naturally by popularity” (p.255). People reposted what they enjoyed and believed others would be drawn to. Chew (2020) collected catch phrases that were reposted throughout different memes that raised the popularity of particular Chinese movie stars. The power of the social media sharing led to a larger box office.

We’ve examined how memes have disrupted political campaigns and are based on popularity, but what happens when it dives into lore that runs Hollywood deep? Before there were memes, there were fan clubs for Nicolas Cage and his outrageously good performances. McGowan (2017) researched how a movie star whose films are just as well-known as his personal life gets immortalized in social media not only by his body of work, but simply from his persona. Some meme campaigns need explanations, other memes can simply post a photo of Nic Cage to hit the mark.

There’s also when the community shares sad memes. M.S. & Burla (2023) discussed how memes of the Joker really open the discussion on mental health. Discussions on identity and representation also matter and come up. Land (2021) spoke about how memes can be used for “circulating counter-discourses to mainstream representations” (p. 182). The community not only allows the rapid-fire spreading of information, it also gives space to marginalized communities. Soegito (2019) surmised it best when he called memes, “‘implications for identity building, public discourse and commentary” (p. 281). In all the different ways that we have looked at this community, simply put, it holds a mirror up to us all.

Methodology

I spend a lot of time behind monitors, if not my work desk, than my television concurrently with my phone. The community-based research I have for this group is myself. I see the memes that pass by on social media and being a lover of film, I immediately get the puns. Being someone who is also interested in the political landscape and with this being an election year, I have been more inclined to follow stories that have to do with politics. How does this tie in with this information community? It means that during the span of this semester, anything I saw on the screen that had to do with memes tied back into this research.

From TikTok to Instagram to watching professionals like Bill Maher use memes on his show, we are inundated with the work of this community constantly. How do you study it? For this, I had to turn to the readings from the semester to better understand how I was digesting the work.

We can look at the research of Mcdonald (2017) and connect it to data collection film memes in that daily events and pop culture connect the community. “It proposes that the individual habits we form when monitoring daily events and seeking information, as well as the sources and channels we use to find information, are based on values, attitudes, and interests learned in sociocultural contexts” (McDonald, p.842). If a meme goes viral for a movie, it must be explored what it was that drew attention to it – was it the film, the joke of the meme on the film, or was it a part of something that happened on that day.

The literature on this community came mostly from researchers that analyze the history of particular films, and those that look at the analytics of how meme groups can be anywhere from grassroots, independent posters, to organizations with corporate and political agendas. The root of this community can be traced to serious leisure. Serious leisure was coined by sociologist Robert Stebbins to describe when people enjoy something so much with their free time that they will dedicate their vacations and even shape their work around it. He wrote, “More circumscribed is the benefit of learning something in an enjoyable setting that could stay with the participant well beyond the visit to that setting, even while no commitment to a serious pursuit result from the experience” (Stebbins, 2015, p. 21).

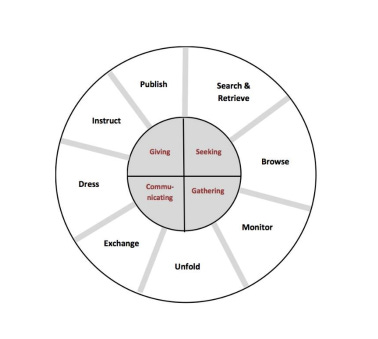

Using the research work of Anders Hektor, Hartel (2003) talked about the four general modes of information behavior. The four modes are giving, seeking, communicating, and gathering. The breakdown of how information is consumed and shared shows it in a human context. (Hartel, 2003, pp. 5-6). The goal was to understand the information activities of people that pursued serious leisure. With all the studies that were conducted around serious leisure and its use in LIS, it always came back to how people tick, meaning, the research always looked for why people chose what they did and then examined how they expressed and explained that activity to others. As if we were watching a movie together and trying to figure out the meaning by the end.

In Hartel’s research, she directly tied serious leisure to LIS work and academic endeavors. “It enables engagement with human subjects who are often passionate, skilled, and thoughtful about their chosen pursuits. More practically speaking, a serious leisure research program may benefit LIS information provision, education, and public identity” (Hartel, 2016, p. 236). This ties into film meme data collectors because film is a form of identity. Most of us own a t-shirt with a film quote or logo on it. What I take away most from the research on the behaviors of this community is that identity plays a huge role. Anything that has to do with our sense of self is important – it’s important to be documented by future generations for history, and we all see how it’s important to political groups and organizations. If a part of us is tied to how we express ourselves in quick online posts, than that time becomes valuable to everyone around us.

Discussion

To have a meaningful engagement with film, “the technical limitations of the different media at different periods; the importance of understanding the detail of the context of production – of why the film was made, who it was for, who paid for it” (Patterson, 2011, pg. 568). By looking at film from this academic perspective, you are revealing the value of film and how it was used and digested by people in real time when the film was first released. This extends into memes in that not only must we understand the film, but the socio-political context of when the meme was created. It delves deep into data collection. I was struck by the work of Booth (2011) who outlined how educational theory can be divided into three main branches: learning, Instructional, and curriculum theories. Utilizing these three branches, film meme data collectors can be broken down by the following:

Learning Theory

Film meme data collectors can be introduced to the archives of film literature in the library. It’s one thing to watch and enjoy all of the films, but when you sit and read through the breakdown of the original literature the film was created from and the biographies of auteurs that created the films, it provides a wealth of information for the community to draw from. An area to highlight for this community would the archives section of any public library. Living in Los Angeles, the Margaret Herrick Library is the beacon of film archives and one can imagine the memes that could be created with the contents of that library.

Instructional Theory

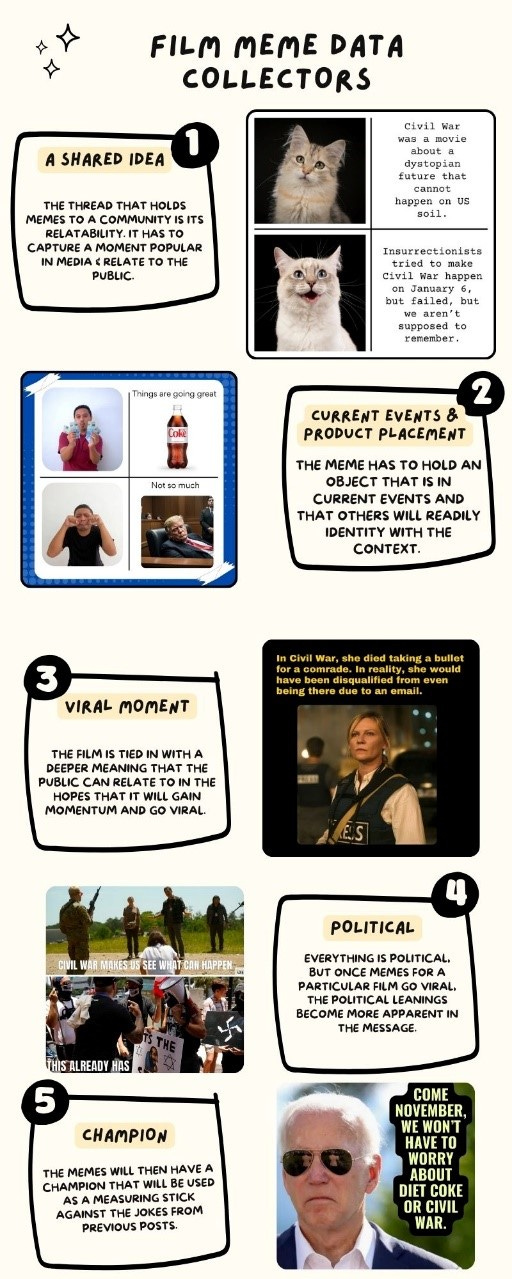

The creativity of memes is unlimited. They can be words on a blank canvas to stills from films used in a way to convey an emotion. Instructional theory ties into this community in that informational professionals can guide them toward making their expression more user-friendly. An innovative technology right now that would be a great tool for the community would be the use of Canva. Its ability to create videos and infographics could be a one-stop shop for this community. They gather the data that they want to use and they create it all on Canva to share with any social media platform. I can see a future where the way that Canva works will turn into an option built into social media sites. Below is an example of a memes that I created using canva to showcase how it could be used.

Curriculum Theory

There is the reflection of the memes by the creator and its readers, but there are also those that archive everything that is being created. It may seem as simple as gathering all memes that relate to a certain film release. Still, after reading through the literature on the community, it can go as deep as pinpointing the start of a political movement. Whatever is utilized to create and can be used to misinform and the place of the information professional is to be as informed as possible on the latest ways of communication – the continued fight against misinformation is the most important.

In conclusion, preserving the views of film by the audience on social media and looking for resource’s ties into the world of information professionals. Whatever the medium, everything we store will mean something down the line, whether it is a scene from a film that only has one existing copy on earth, or a new student learning to search for said information in databases and creating their self-expression on Canva.

Conclusion

This long winding path through film and memes has given me the history of the community, which is anyone that has access to the Internet and likes to share ideas with others. The knowledge gained about the community is really how it’s being utilized globally. There are countries that have control of their social media platforms to control what content it released, whether it be for movies or political candidates. Corporations are flooding the Internet with product-based memes that they can gain from. A way of communicating that has caught on to the general public is now being incentivized and politicized.

What can information professionals do for this community? They can provide resources in the library from archives, films, to the use of our computers and software. The greatest task at hand will be in fighting misinformation. It was shocking to read about how public opinions are being swayed by the use of memes for different demographics. Information professionals will see in real time how this plays out and will be at the forefront of ensuring that patrons have access to information and the ability to express their beliefs on that information.

The research on this community is young, but it’s growing and it will be interesting to see how it plays out and how much more traction it gains with the general public.

References

Alipate, S.M. (2024) Film Meme Data Collectors. Meme created on Canva.com (24 April 2024).

Booth, Char. Reflective Teaching, Effective Learning: Instructional Literacy for Library

Educators, American Library Association Editions, 2010. ProQuest Ebook Central, https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/sjsu/detail.action?docID=675848.

Braid, B. (2017). The Frankenstein meme: penny dreadful and the Frankenstein chronicles as

adaptations. Open Cultural Studies, 1(1), 232–243. https://doi.org/10.1515/culture-2017-

0021

Burke, L. (2022) “Cosplay as Vernacular Adaptation: The Argument for Adaptation Scholarship

in Media and Cultural Studies.” Continuum (Mount Lawley, W.A.), 36 (1), pp. 84–

101, https://doi.org/10.1080/10304312.2021.1965958

Chew, M. “Discovering the Digital Stephen Chow: The Transborder Influence of

Chow’s Films on the Chinese Internet in the 2010s.” Global Media and China, vol. 5, no. 2, 2020, pp. 124–37, https://doi.org/10.1177/2059436420928058

Eastman, S.L. “Mark Twain’s ‘The War Prayer’ in Film and Social Media.” The Mark

Twain Annual, vol. 14, no. 1, 2016, pp.78–92, https://doi.org/10.5325/marktwaij.14.1.0078

Faidley, E.W. (2021) “Movies, tv shows, and memes... oh my!’: An honors education through

popular culture and critical pedagogy.” Honors in Practice, vol. 17, 2021, pp. 145-158.

Foster, M. E. “Women’s Voices in Digital Media: The Sonic Screen from Film to Memes.

Jennifer O'Meara. U of Texas P, 2022. 272 Pp. $24.00 Paper.” Journal of Popular Culture, vol. 56, no. 2, 2023, pp. 398–400, https://doi.org/10.1111/jpcu.13245

Hartel, J., (2003). The serious leisure frontier in library and information science. Knowl.org

30(3/4). Pp. 228-238. https://doi.org/10.5771/0943-7444-2003-3-4-228

Hirsch, G. “Hitler’s out of Dope: A Cross-Cultural Examination of Humorous Memes.” Journal

of Pragmatics, vol. 149, 2019, pp. 25–39, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2019.06.003

Holmene, I. “Paid or Semi-Public Media? The Norwegian Film Industry’s Strategies for

Social Media.” Northern Lights (Copenhagen), vol. 16, no. 1, 2018, pp. 41–57, https://doi.org/10.1386/nl.16.1.41_1

Land, J. (2021) “’Since Time Im-MEME-Morial’!: Indigenous Meme Networks and Fan-

Activism.” JCMS : Journal of Cinema and Media Studies, vol. 60, no. 2, 2021, pp. 181–86, https://doi.org/10.1353/cj.2021.0012

Lee, A., and King, F.D. (2015) “From Text, to Myth, to Meme: Penny Dreadful and

Adaptation.” Cahiers Victoriens & Édouardiens, vol. 82, no. 82 Automne, 2015, pp. 9-,

https://doi.org/10.4000/cve.2343

M, S. P., & Burla, V. N. (2023). Joker memes as a form of expressing inner thoughts: a character

analysis of joker with reference to the theatre of cruelty. ShodhKosh: Journal of Visual and Performing Arts, 4(2). https://doi.org/10.29121/shodhkosh.v4.i2.2023.623

McGowan, D. (2017). Nicolas Cage – good or bad? stardom, performance, and memes in the age of the internet.” Celebrity Studies, 2017, https://doi.org/10.1080/19392397.2016.1238310

Nee, R.C., and Maio, M. (2019). “A ‘Presidential Look’? An Analysis of Gender

Framing in 2016 Persuasive Memes of Hillary Clinton.” Journal of Broadcasting &

Electronic Media, vol. 63, no. 2, 2019, pp. 304–21, https://doi.org/10.1080/08838151.2019.1620561

O’meara, J. (2018). “Meme Girls Versus Trump: Digitally Recycled Screen Dialogue as Political

Discourse.” The Velvet Light Trap, vol. 82, no. 82, 2018, pp. 28–42,

https://doi.org/10.7560/VLT8204

Pang, N. & Goh, D.P. (2016). Are we all here for the same purpose? Social media and

individualized collective action. Chin Online Information Review. 40(4) pg.544 – 559

Patterson, J.M. (2011). Afterword: film as research resource – response from the

perspective of the archivist. Paedagogica Historica. 47 (4), pg. 567-571. https://doi.org/10.1080/00309230.2011.589392

Penney, J. (2020) “‘It’s So Hard Not to Be Funny in This Situation’: Memes and Humor in U.S.

Youth Online Political Expression.” Television & New Media, vol. 21, no. 8, 2020, pp. 791–806, https://doi.org/10.1177/1527476419886068

Pop, D. (2015). Puerile Patriarchs of an Infantilized God. Mythological Meme Mutations in

Contemporary Cinema. Caietele Echinox, 28, 253–280.

Schmidt, L. (2021). “Aesthetics of Authority: ‘Islam Nusantara’ and Islamic ‘Radicalism’ in

Indonesian Film and Social Media.” Religion (London. 1971), vol. 51, no. 2, 2021, pp. 237–58, https://doi.org/10.1080/0048721X.2020.1868387

Soegito, A. (2019). “Fans vs. Critics: Challenging Critical Authority through Memes.” Journal

Of Fandom Studies, vol. 7, no. 3, 2019, pp. 279–301, https://doi.org/10.1386/jfs_00005_1

Stebbins, B., (2015 June 11). Leisure reflections 39: On edutainment as serious hedonism.

Leisure Studies Association.

https://leisurestudiesblog.wordpress.com/2015/06/11/onedutainment-as-serious-hedonism/

Turner-Kilburn, E.J. (2022). “Reimagining Queer Female Histories through

Fandom.” Transformative Works and Cultures, vol. 37, 2022, https://doi.org/10.3983/twc.2022.2109